Frontal Sinus Stenting Techniques

Background

Endoscopic surgery is now commonly used in the management of simple and complex pathologies of the frontal sinus. As experience with the endoscopic technique has grown, use of these procedures for frontal sinus surgery has increased. The goals of endoscopic frontal sinus surgery include disease eradication, implementation and maintenance of an adequate drainage and ventilation pathway, and the restoration of mucociliary function.

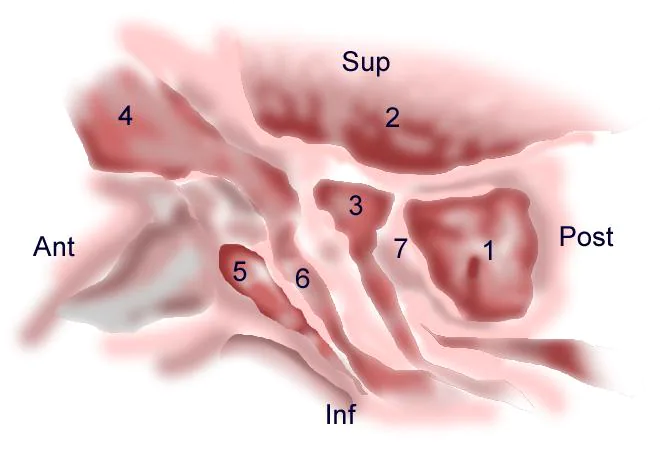

Frontal sinus pathology is particularly challenging to treat due to the narrow and complex anatomy of the frontal outflow tract (see the images below).

Anatomy of the lateral nasal wall, schematic: (1) Sphenoid sinus, (2) anterior cranial fossa, (3) anterior ethmoid cell, (4) frontal sinus, (5) agger nasi, (6) infundibulum, (7) posterior ethmoid cell

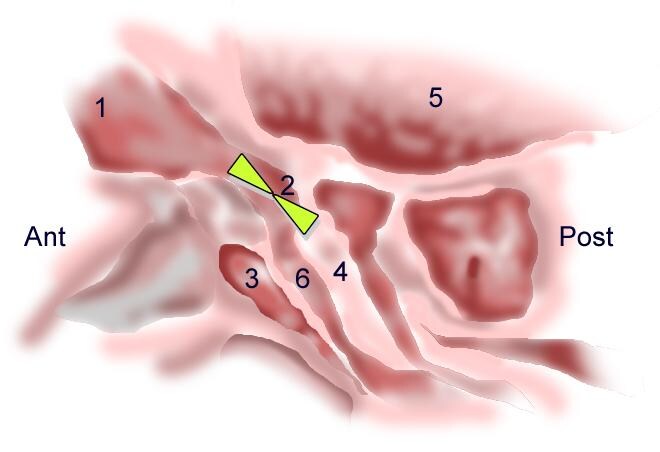

Anatomy of the frontal recess. The frontal recess is an hour glass-shaped space (green shaded area) with the waist at the frontal ostium and its narrowest part that drains into the ethmoid infundibulum: (1) frontal sinus, (2) frontal ostium, (3) agger nasi cell, (4) bulla ethmoidalis, (5) anterior cranial fossa, (6) infundibulum

Stenosis of the frontal recess or failure to establish a tract can lead to disease persistence and iatrogenic complications. Postoperative stenosis of the frontal sinus outflow due to formation of scar tissue, synechiae, or osteogenesis is the most common cause of frontal sinus surgery failure.

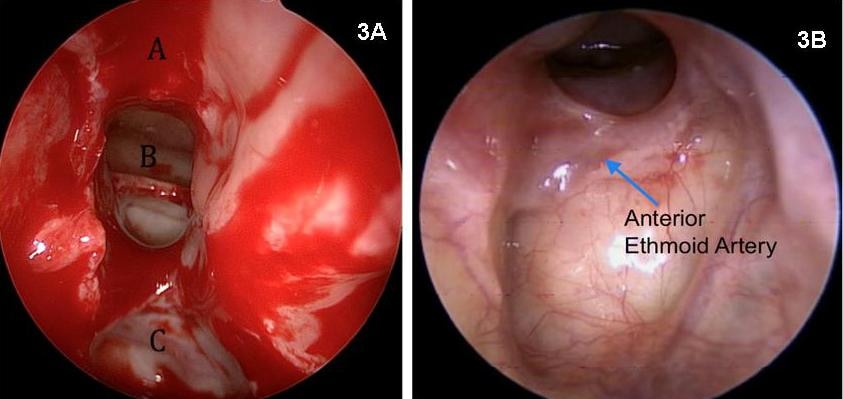

Stenosis of the frontal recess is best prevented by avoiding unnecessary manipulation of the outflow tract and meticulous surgical technique. Without formal frontal ostium dissection, anterior ethmoidectomy with exposure of the frontal recess has been shown to result in resolution of frontal sinus disease. The indications for a formal frontal sinusotomy should therefore be carefully determined. If frontal recess dissection is undertaken, meticulous tissue handling with avoidance of any mucosal trauma is key to a successful outcome. Routine frontal stenting is unnecessary (see image below).

3A: Intraoperative endoscopic view of the dissected frontal ostium after total anterior ethmoidectomy and Draf 2a frontal ostioplasty (70º endoscope view): (A) nasal beak, (B) frontal neo-ostium, (C) anterior skull base. Postoperative view of frontal ostium with a 70º endoscope. 3b: Well-healed, mucosalized frontal neo-ostium 3 months after Draf 2a (frontal ostioplasty). No stent was used in this case.

The most common cause of restenosis of the frontal sinus outflow tract is iatrogenic (postoperative scarring, adhesions, and middle turbinate lateralization). Severe inflammatory pathology, obstructive polyposis, and nonsurgical trauma are other common causes.

The incidence of persistent frontal sinusitis with symptoms after endoscopic sinus surgery is 2-11% based on numerous studies, all with relatively short follow-up. The necessity of longer follow-up after frontal sinus surgery to determine the true incidence of disease relapse was demonstrated by Neel et al. In their study, failure rate after modified Lynch procedure increased from 7% at 3.7 years to 30% at 7 years. Frontal sinus stenting may help prevent failure of standard endoscopic treatment of frontal sinus disease by maintaining patency and structural integrity of the frontal sinus outflow tract while regeneration of the frontal neo-ostium mucosal lining takes place. In many situations, such as after a drill-out procedure (modified Lothrop or Draf III) for neo-osteogenesis or tumor removal, the mucosal lining is absent or significantly violated. Stenting may be useful in such situations.

Surgically placed stents to maintain ventilation and drainage of the frontal sinuses have been used for over a century. The first frontal sinus stents were gold tubes used in 1905 by Ingals. In 1921, Lynch first described his frontoethmoidectomy technique, of which a key component was 1-cm rubber tubing used to stent the frontal sinus. Progress in both surgical instrumentation and new stent material has been made over subsequent years. Numerous options are now available for stenting in cases that have an anticipated high risk of surgical failure. Stents differ in terms of material, shape, and the techniques used to deploy them.